On Wednesday, Dec. 30, 2015, the Allstate Sugar Bowl Fan Fest at 418 North Peters Street will begin at noon and last throughout the day leading up to a concert performance by Usher beginning at 6:15 p.m. NOPD officers will be monitoring pedestrian crowds in the French Quarter and will divert vehicular traffic if necessary.

Allstate Sugar Bowl Parade

On Thursday, Dec. 31, 2015, at 3:30 p.m., the Allstate Sugar Bowl Parade begins at Elysian Fields and Decatur Street, proceeds down Decatur Street, past Jackson Square and the Allstate Fan Fest at 418 North Peters Street, disbanding at Canal Street.

2016 New Year’s Eve Celebration

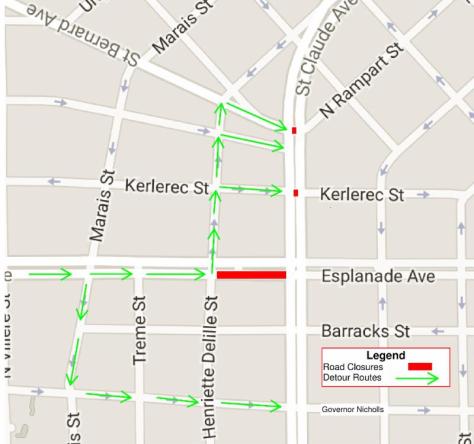

On Thursday, Dec. 31, 2015, in preparation for the 2016 New Year’s Eve concert and countdown celebration in front of Jackson Square, Decatur Street will be limited to one lane of traffic each way from Dumaine Street to St. Louis Street until approximately 2:30 a.m. Friday, Jan. 1, 2016.

NOPD officers will be monitoring the pedestrian crowd and will divert vehicular traffic from Decatur Street/ South Peters Street, between Canal Street and Esplanade Avenue, if necessary. NOPD anticipates a large pedestrian crowd and encourages drivers to avoid this area.

2016 Allstate Sugar Bowl

On Friday, Jan. 1, 2016, for the Allstate Sugar Bowl, NOPD officers will be monitoring pedestrian crowds in the French Quarter and will divert vehicular traffic if necessary.

Parking enforcement personnel will be monitoring for illegal parking, including blocking hydrants, driveways and sidewalks, or parking within 20 feet of a crosswalk, intersection or stop signs. Motorists are also reminded to park in the direction of travel on one-way streets and with the right wheel to the curb on two-way streets.

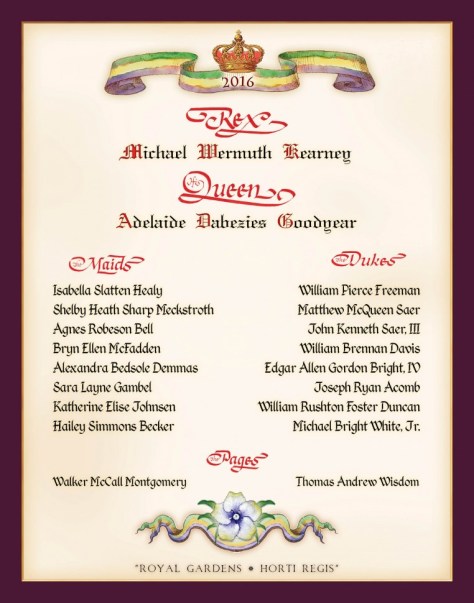

This year’s theme is presented both in English (“Royal Gardens”) and in Latin (“Horti Regis”), emphasizing the timeless significance of gardens. The desire to be surrounded by beauty is as old as mankind itself. In every time and culture artists have arranged natural elements into gardens to please all of the senses. Emperors and Kings assured that their gardens were planned with as much care as their castles, and some of these gardens were counted among the wonders of the world. The 2016 Rex Procession takes us to splendid gardens known only from ancient illustrations and descriptions, and to others still providing beautiful sights to those who visit them. In the best tradition of Rex artistic design, watch for a parade filled with colorful flowers, historic figures, and colorful costumes.

This year’s theme is presented both in English (“Royal Gardens”) and in Latin (“Horti Regis”), emphasizing the timeless significance of gardens. The desire to be surrounded by beauty is as old as mankind itself. In every time and culture artists have arranged natural elements into gardens to please all of the senses. Emperors and Kings assured that their gardens were planned with as much care as their castles, and some of these gardens were counted among the wonders of the world. The 2016 Rex Procession takes us to splendid gardens known only from ancient illustrations and descriptions, and to others still providing beautiful sights to those who visit them. In the best tradition of Rex artistic design, watch for a parade filled with colorful flowers, historic figures, and colorful costumes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.