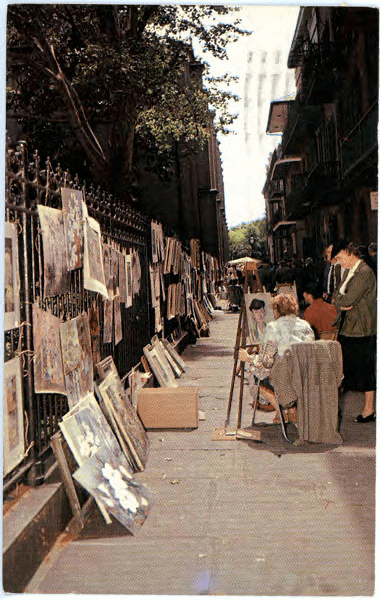

It is once again time (11th year!) for me to climb the small fruit tree at the corner of the BK museum garden, pick what is reachable, and answer a LOT of questions from passers by.

(2016) Over the years, I have kept an eye on the citrus tree in the corner of the garden of Mrs. Parkinson-Keyes’ house at Ursuline and Chartres, which looks like a kumquat tree. Some years, it is so laden down with fruit in January that it hangs low enough to pick some on the street side. Almost all winter, the sidewalk is slick with fallen fruit, mushed by the feet of those on their way to Croissant D’Or or to Royal Street and beyond.

A little over a year ago, I decided to contact the director of the Beauregard-Keyes Museum to see if they would allow me to pick the fruit. I emailed them and almost immediately received a reply, “Dear neighbor, I received your request to pick our tree-but I must tell you that it is not a kumquat, but a calamondin tree. If you still would like the fruit, feel free to come in the garden after we open each day and help yourself! We only pick a small amount around the holidays to put on gifts so there is always plenty.”

After looking up calamondins, here is what I found:

Camondin, Citrus mitis, is an acid citrus fruit originating in China, which was introduced to the U.S. as an “acid orange” about 1900. This plant is grown more for its looks than for its fruit edibility and performs well as a patio plant or when trimmed as a hedge. It is hardy to 20 degrees F. and is hardier to cold than any other true citrus specie—only the trifoliate orange and the kumquat are more tolerant to low temperatures. The edible fruit is small and orange, about one inch in diameter, and resembles a small tangerine.

The fruit is smaller than a typical lime, have a thinner skin, and seem best used within a week after harvest if not refrigerated. When picking the fruit, it is best to use clippers or scissors to get them off of the tree, rather than pulling them. This will keep the stem end of the fruit from tearing, which promotes deterioration.The juice of the calamondin can be used like lemon or lime to make refreshing beverages, to flavor fish, to make cakes, marmalades, pies, preserves, sauces and to use in soups and teas. The juice can be frozen in containers or in ice cube trays, then storing the frozen cubes in plastic freezer bags. Use a few cubes at a time to make calamondinade. The juice is primarily valued for making acid beverages. It is often employed like lime or lemon juice to make gelatin salads or desserts, custard pie or chiffon pie. In the Philippines, the extracted juice, with the addition of gum tragacanth as an emulsifier, is pasteurized and bottled commercially. This product must be stored at low temperature to keep well. The juice of the calamondin also makes an excellent hair conditioner. Pour 1 liter of boiling water over thinly sliced fruit. Let it steep. When water is cool, pour through the hair as a final rinse. The fruit juice is used in the Philippines to bleach ink stains from fabrics. It also serves as a body deodorant. Rubbing calamondin juice on insect bites banishes the itching and irritation. It bleaches freckles and helps to clear up acne vulgaris and pruritus vulvae. It is taken orally as a cough remedy and antiphlogistic. Slightly diluted and drunk warm, it serves as a laxative. Combined with pepper, it is prescribed in Malaya to expel phlegm. The root enters into a treatment given at childbirth. The distilled oil of the leaves serves as a carminative with more potency than peppermint oil.

I asked a few of my foraging friends if they wanted to come along and my chef pal Anne Churchill is the one person who almost always takes me up on it. She and I bring a ladder in her old creaky truck and climb up with bags (actually she brings bus tubs from her kitchen) and snip away. We catch up as we work and discuss the health of the tree and answer questions from passersby.

Over the last few years, I have harvested 3-5 gallons of citrus at least 8-10 times, as has Anne. I make it into syrups and share that and the fruit with friends, including the chef at Meauxbar, Kristen Essig, who I used to work with at the farmers market organization.

Today, I actually bought my 10-foot tree pruner and cut more of the old growth away and more from the street side: being alone this time and on that side meant I had many more interactions, including a scowling neighbor who asked if I had permission, one of the museum volunteers who seemed confused by my explanation that I was a neighbor and not their landscaper and many visitors who wanted to know more about the tree, about the house and about other random things.

It is my great pleasure to work in the sun, in my beautiful neighborhood and share the bounty of the trees and plants put here by our previous generations.

They just added this bower for a recent event, likely a wedding.

A close up of one of the calamondins

December’s haul (actually half of it) as I wash the fruit first

Cooking the calamondins. I cook them for a very long time, with honey, cayenne pepper and satsuma juice added.

Finished product

Me up in the tree in 2014

You must be logged in to post a comment.