Just like the French Quarter itself, the style of the public markets in New Orleans has more to do with the Spanish and American eras than the French. In 1763, when the Spanish gained the tiny French colony, the population of New Orleans was only around 3,500 and no permanent market building yet existed, although open-air commerce had long operated at the river. In 1791, the city’s Spanish administrators built a market at present-day Decatur and Saint Ann, after first attempting one at the corner of Chartres and Dumaine. The Halle des Boucheries – the Meat Market – erected in 1813 still exists (where the market’s longest tenant, Café du Monde has operated since 1862), accompanied for a few decades by architect Henry Benjamin Latrobe’s water works and by market buildings built in the years 1822-1872.

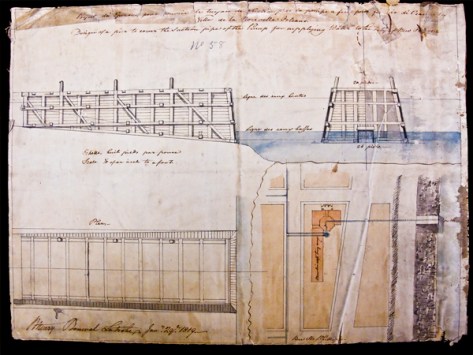

A 1819 architectural rendering depicting the design of a pier to cover the suction pipe of the pump for supplying water to the City of New Orleans by Benjamin Latrobe who helped design the US Capitol and is considered the father of American professional architecture. Sadly, Latrobe died of yellow fever while building this system.

This area stretching along the river at the “back” of the Quarter became known as the French Market in the 19th century, undergoing a renovation in the 1930s thanks to the New Deal, again in the 1970s and in 2005/ 2006, each renovation further erasing more of the original building layout and any visible reminders of their use. Luckily, the number of descriptions devoted to the market by visiting dignitaries still combine for a detailed and lively view. Latrobe wrote in his journal in 1819:

“Along the levee, as far as the eye could reach to the West and to the market house to the East were ranged two rows of market people, some having stalls or tables with a tilt or awning of canvass, or a parcel of Palmetto leaves. The articles to be sold were not more various than the sellers … I cannot suppose that my eye took in less than 500 sellers and buyers, all of whom appeared to strain their voices, to exceed each other in loudness….”

And another in 1874:

“New Orleans’ French Market had more tropical merchandise, including bananas, pineapples, coconuts, oranges, and limes as well as an amazing variety of shellfish, including crab, lobster, shrimps, and “enormous oysters, many of which it would certainly be of necessity to cut up into four mouthfuls, before eating,” reported Charles Dickens in All the Year Round.

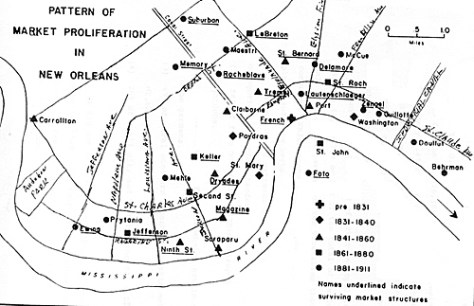

Since that first market, another 33 were to join it by the 1940s. This gave New Orleans the largest market system in the U.S., with only Baltimore as a serious competitor, according to author Helen Tangires in her landmark book “Public Markets and Civic Culture in Nineteenth-Century America.”[1] The list of the city’s markets is a history and geography lesson of its neighborhoods and civic leaders: St. Mary, Poydras, Washington, Carrollton, Ninth Street, Soraparu, Magazine, Dryades, Claiborne, Treme, St. Bernard, French, Port, Jefferson, Second Street, Keller, LeBreton, St. Roch, St. John, Ewing, Prytania, Mehle, Memory, Suburban, Rocheblave, Maestri, Delamore, McCue, Lautenschlaeger, Zengel, Guillotte, Doullut, Behrman and Foto. Local market historian Sally K. Reeves [2] wrote, “ These well-dispersed centers of food and society played an essential role in the city’s cultural, economic and political life. They also generated their share of crime, grafts, rule defiance and contract disputes.”

Only some of these buildings remain (around 15 as of 2005) with only two still operating as city-owned public market buildings: the French Market and the St. Roch Market, both down river of Canal Street, and only a few blocks from each other. The St. Roch Market escaped the auction block in the 1930s through neighborhood pressure and was recently reborn as a controversial food hall after Hurricane Katrina. Before 2005, it spent decades under private, half-hearted use that closed off most of the building to use. Besides those two, the only other that operates in some manner close to its beginnings is what had been the St. Bernard Market and is now a grocery store known as Circle Food, also only a few blocks from the others. Walking through its colonnade, one notes its practical market design and appreciates the superb retail location at the intersection of Claiborne and Saint Bernard Avenues. This store serves the 6th, 7th and 8th ward Creole community primarily, but also shoppers across the region looking for foods known to New Orleans families of every ethnicity. From the current Circle Food site: “coons, rabbits, pig ears & lips, turkey necks & wings, ham hocks, chicken feet, cow tongue, lunch tongue, beef kidney, oxtails, and special fresh cuts of veal including veal seven steaks.”

In her 2005 University of New Orleans thesis on food and markets, researcher Nicole Taylor traced each remaining public market building in the city and its current use. Some of the buildings have even retained their WPA-era plaque to remind passersby of its market history.

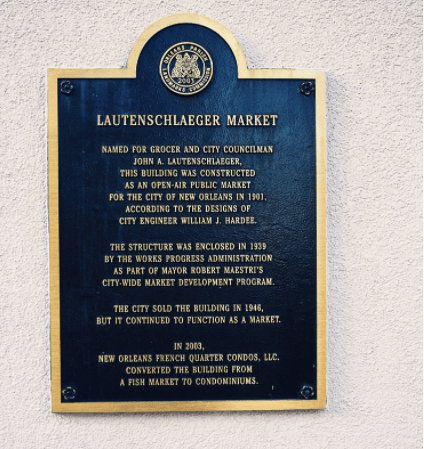

LAUTENSCHLAEGER MARKET Photo: John W. Murphey © Creative Commons BY-NC-ND

She noted in her analysis, “The changing values in American planning and development did affect New Orleans, only more slowly. The Depression years brought change in New Orleans with some large projects conducted by the WPA, but the markets were not replaced, only renovated. While the rest of the country was beginning to demolish old neighborhoods and replace the old homes and storefront businesses with modern buildings, high rises and highway systems in the name of progress, New Orleans’ operation of municipal public markets continued[3].”

Finally, the 20th century collapse of the public market system in the U.S. assisted by the emergence of refrigeration and the supermarket came to New Orleans and the city began to sell off its magnificent markets, leaving its vendors to an uncertain fate. Many set up permanent stores nearby, with some even continuing their original business to this day. But not until the modern farmers market revival arrived in New Orleans in 1995 with the first open-air Crescent City Farmers Market did significant numbers of farmers, fishers and foragers begin to trickle back from outlying parishes to once again sell their goods. The CCFM organizers even spirited away the last few farmers still selling at the old French Market, leaving New Orleans’ original market only suitable for tourists. In 2003 however, CCFM arranged for the return of farmers to the French Market by offering a regular Wednesday market in the 1930s-era Farmers’ Market shed. The French Market Corporation, the private/public corporation that has formally managed the market district for the city since the early 1930s, also began to search for other artisanal entrepreneurs to operate permanent stalls on either side of the aisle. The effort has not been entirely successful in luring locals back but it is important to note that besides the farmers market on Wednesdays, the French Market now includes a local artists co-op, respected cooperative and healthy cafes, a thriving artist colony around Jackson Square, a cooking demonstration stage and regular cultural events on site.

The upshot is that unlike most other American cities, New Orleanians can participate in the same public market tasks as previous generations, including at the same spaces used for that activity since the city was new.

The 1878 Hardee map of New Orleans, showing many of the markets.

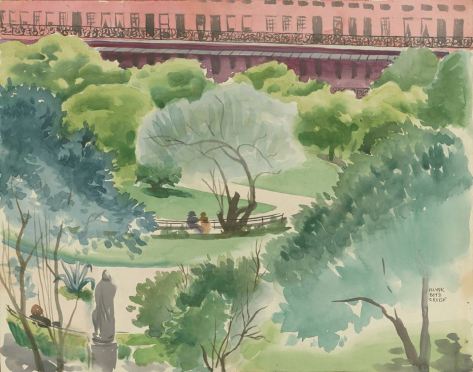

A pic that historian Richard Campanella posted of a 1930s renovation design idea of the St. Roch market that was never used.

The interior of St. Roch Market after the WPA renovation

Photographer Roy Guste shot the inside of the St. Roch as the city began to renovate it in 2012.

The Saturday Crescent City Farmers Market in its new location as of October 2016. It spent exactly 21 years at the corner of Magazine and Girod before moving to Julia and Carondelet. These open-air markets only allow producers and harvesters to sell directly; no resellers allowed.

[1] Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003

[2] Author of “Making Groceries: A History of New Orleans Markets.” Louisiana Cultural Vistas 18, no3. Also author of upcoming book on New Orleans public market system.

[3] Taylor, Nicole, “The Public Market System of New Orleans: Food Deserts, Food Security, and Food Politics” (2005). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. Paper 250.

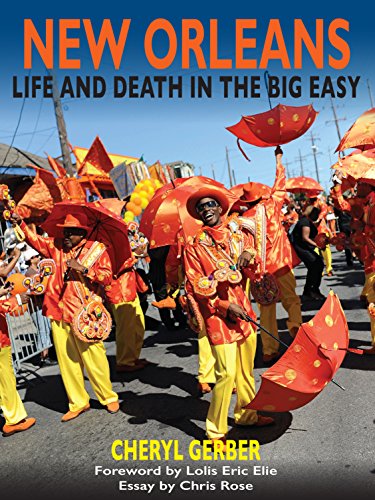

Of course I had noted Gerber’s pictures before, but like so many of our “journeyman” photographers, her work has most often been published in our ephemeral media and with that comes a tiny name credit all that marked it as hers, likely often missed. And oddly for such a visual city, the writer of words is usually given prominence over those who use a camera. It’s not that photographers are never celebrated: Gerber’s own photography mentor Michael Smith is renowned as are at least a half dozen or more names. But since working photographers are thankful to get one shot at a time published, it is often only when you see a number of photos together that the individual’s viewpoint emerges.

Of course I had noted Gerber’s pictures before, but like so many of our “journeyman” photographers, her work has most often been published in our ephemeral media and with that comes a tiny name credit all that marked it as hers, likely often missed. And oddly for such a visual city, the writer of words is usually given prominence over those who use a camera. It’s not that photographers are never celebrated: Gerber’s own photography mentor Michael Smith is renowned as are at least a half dozen or more names. But since working photographers are thankful to get one shot at a time published, it is often only when you see a number of photos together that the individual’s viewpoint emerges.

You must be logged in to post a comment.